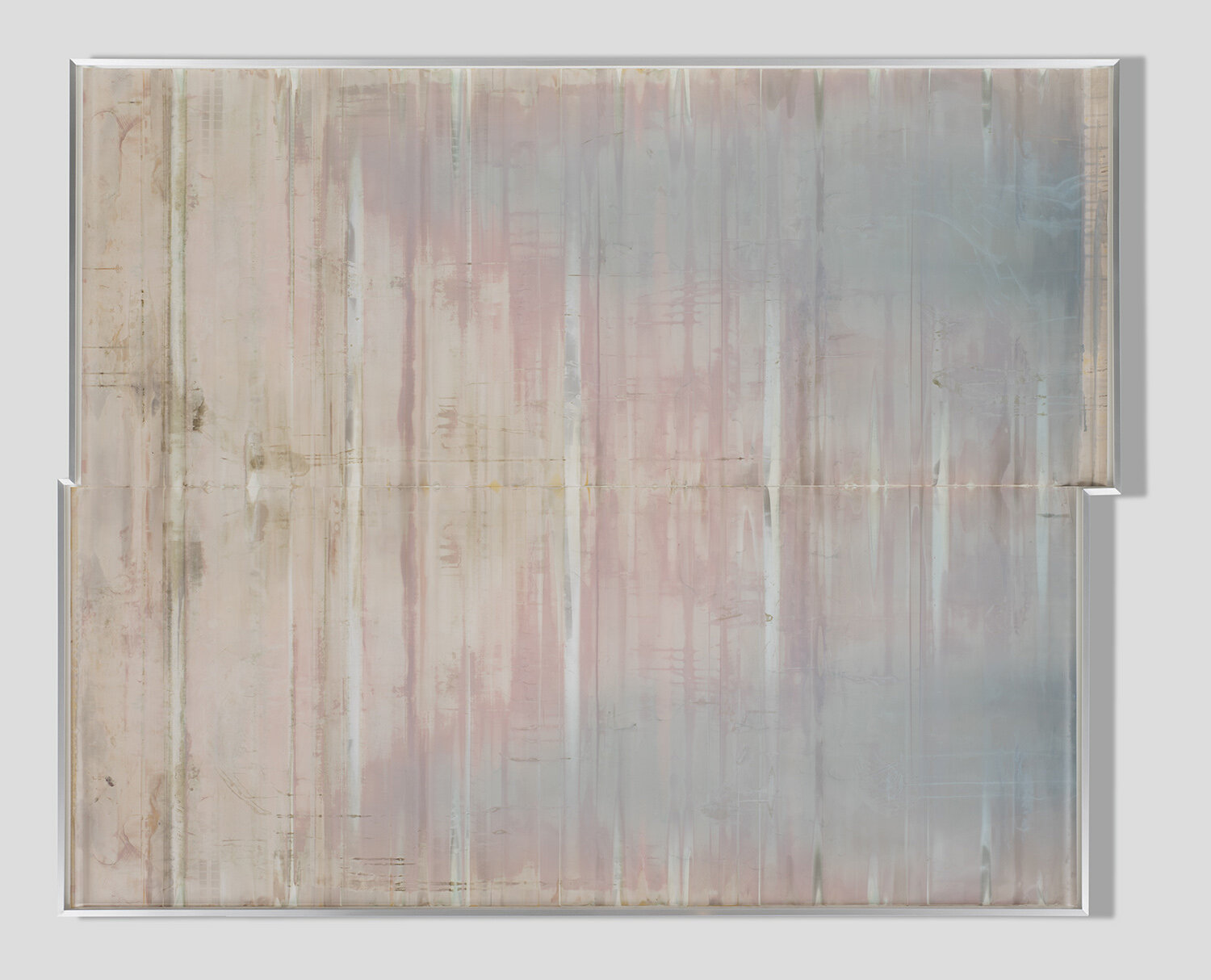

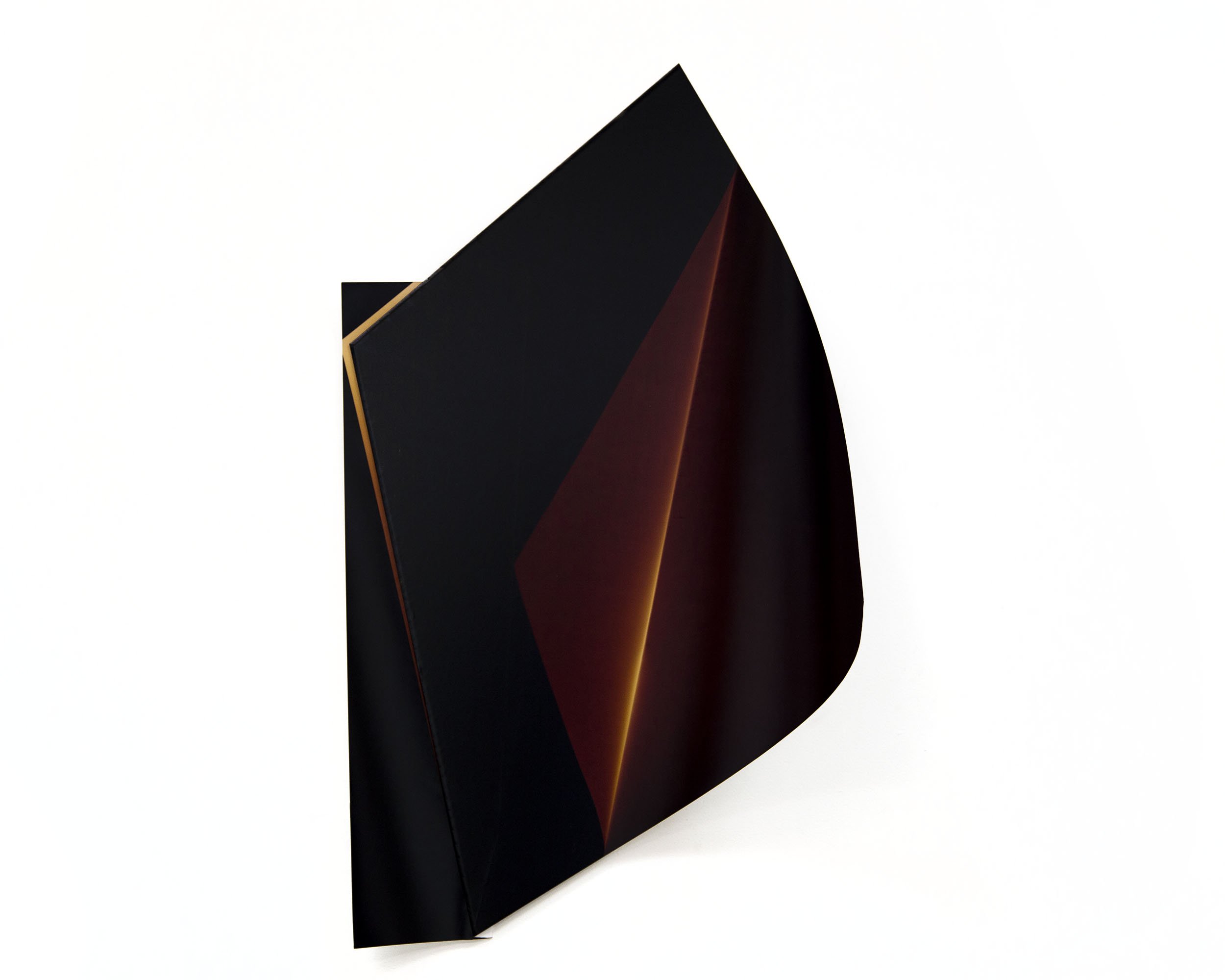

Non-Pictorial Photographic Works

2005–

On the Use of the Term “Image”:

“Images” have no sides, nor dimensionality. They have no back or front. They are theoretical objects, not material ones. “Image” (imago) means “likeness,” it is a propositional term describing a posited relation between two things, not a thing in itself. Using the term to refer to an object lends the term a false solidity, while making that object ephemeral, relegated to nothing more than a likeness, fantasizing the concrete world into phantasmagoria, and life itself into apparition.

On the Use of the Term “Picture”:

The term “picture” refers to a subset of “images” and only describes representational qualities, not the material existence of an object in the real world. A “picture” is an organizational logic (i.e. a schematization) used to produce a likeness, or image; it is a form, or convention for producing a likeness, and it is always synthetic. Whereas an image can be made by chance (as in a fossil, or other natural phenomena), a picture requires the human application of an abstract logic upon the world. Thus, “pictures” have no specific scale; they can be any size, exist in any material, and still be the same picture as long as they have the same pictorial form. A photograph reproduced on a billboard and as an advertisement in a magazine would be called the same “image/picture” despite the fact that the way they are produced, the way they are trafficked, the relationship to a viewer, their context, and the materials used are completely different. When we describe objects as images or pictures, we obscure the concrete conditions surrounding the reception of aesthetic information.

On the Use of the Term “Abstraction”:

The term “abstraction” is generally misused in art to refer to non-figurative work; this is a misleading application of the term. Any work referred to as “abstract” is, by the application of that term alone, set apart from the world, isolated from the world of objects, and construed as having a “meta” relationship to the world and its context. The term “abstraction” names an interpretation of the object, not a characteristic of the object. In other words, one can claim an object is “abstracted” from some external circumstance, but the object on its own cannot support such a claim. Thus, the problem with the term is two-fold: it is first misapplied within an art context to describe works that are non-figurative and, more insidiously, it presumptively ascribes an aspect of interpretation to the object, turning an instrumentalization of the object into an ontological characteristic of it. In this, the problems associated with the conventional use of the term “abstraction” are similar to those described above for the terms “image” and “picture.” In each case, the term describes a relationship between objects, and in the misuse of each, a relational term becomes a definitive term.

General Comments on the Production of Non-Pictorial Photographic Works:

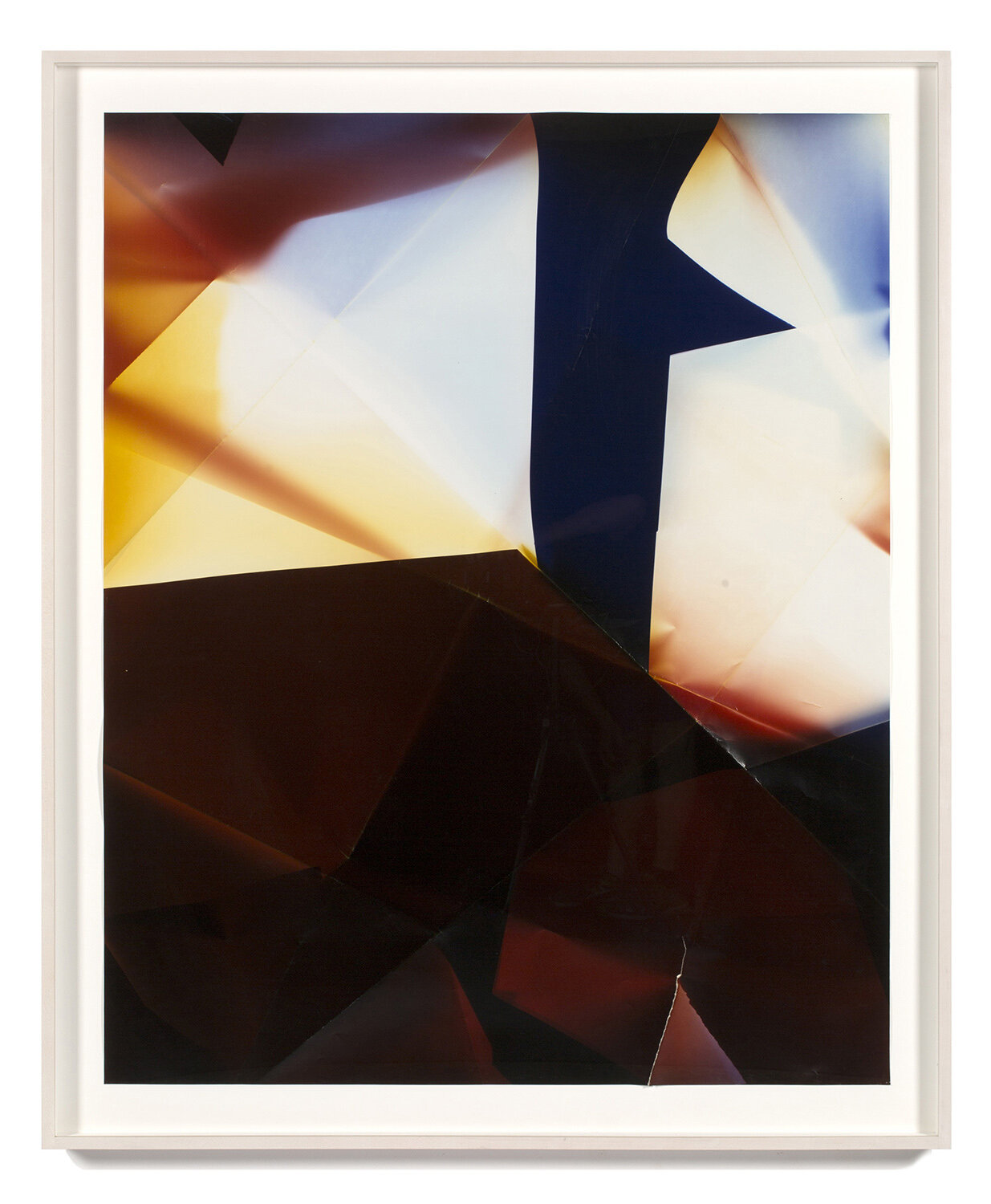

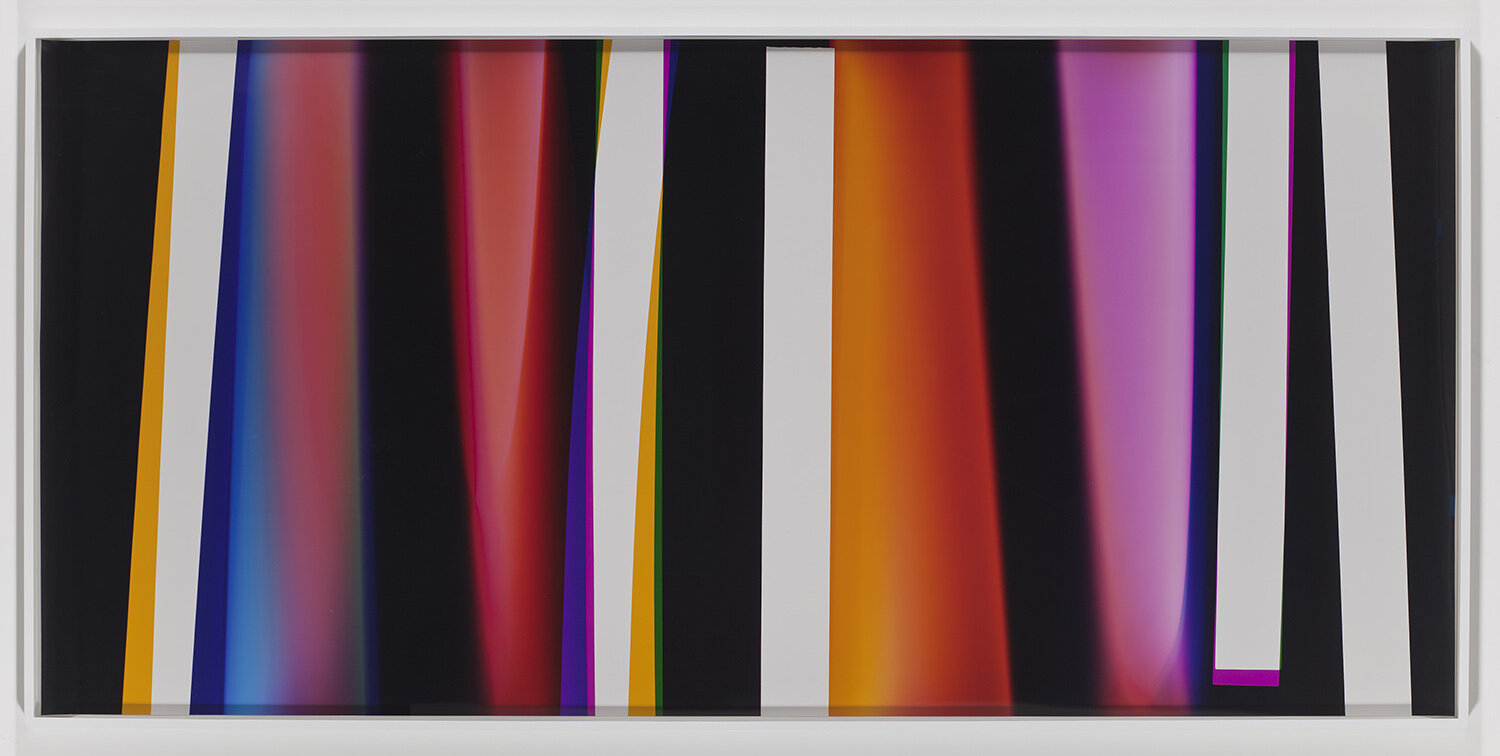

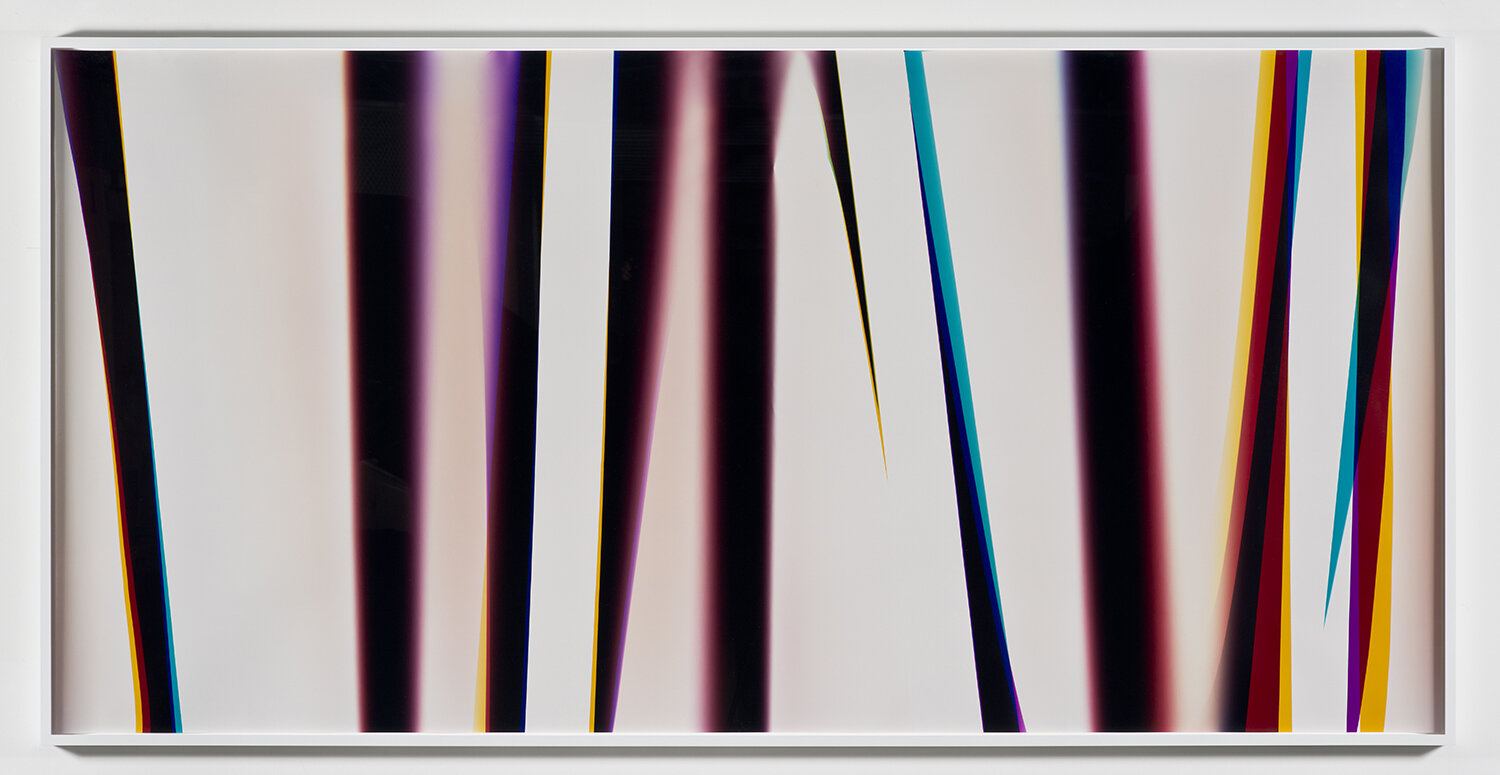

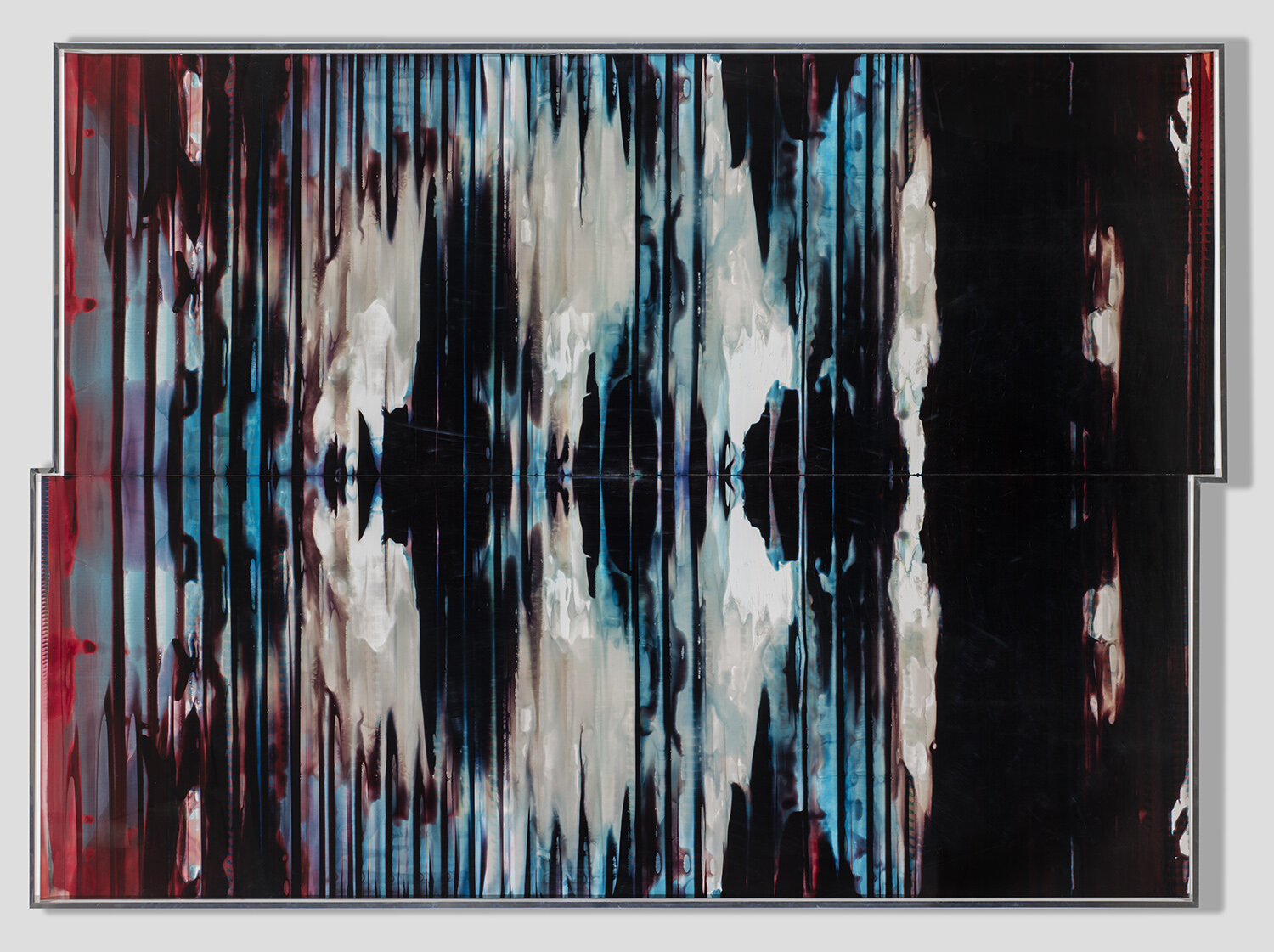

The non-pictorial photographic works began out of an attempt to collapse the distinction between depictions and their material support by using the paper itself to define the forms. Depending on the size of the paper, the forms on its surface will be different (whether they are curled, folded, or crumpled), because each piece of paper is only manipulatable in ways that are specific to it. The weight, tooth, and scale of the paper directly impact the forms that appear on the surface of the paper. Unlike the “picture” that adheres to an abstract logic (such as Renaissance perspectival rules that are based on the construct of homogeneous and infinite Cartesian space), these pictures—because the medium that receives the images is bent—are anisotropic. Anisotropic images are irregular in every direction, unlike the homogeneous space of Renaissance perspectival form, and they do not indicate stable relations of scale or position because they assert a logic that is specific to their confines, thus they cannot be used to indicate an order to be applied to the circumstances outside of their own production, i.e. they cannot propose to “map” or “order” the world outside of their boundaries, and thus do not set themselves apart from the world, but exist as part of the world. The distinction between what is represented on the surface of the photograph and the photographic material is removed (unlike a normal photograph, where the picture and the material support are kept conceptually separate). Furthermore, the paper acts like a conventional negative (incidentally, the first negatives were paper- based), casting an image of itself onto itself; the negative and the photographic paper are one and the same, further eliminating the separateness of ”image” and material. This causes some instances where a literal fold or curl in the paper is echoed by a shape describing that fold or curl, while in other instances, this produces shapes that are not directly manifest in the topography of the paper. In the instances where the form shown on the surface is discontinuous with the surface the form is on, the paper has served as a “negative” that produces an image of itself on its surface. It could be said that the paper cast a shadow of itself onto itself, and because the paper is photographic, this momentary “shadow” can be fixed in place.

On the Artist as a Material Condition of the Work:

The exposure process for these works must either occur within total darkness (in the case of the color works) or under safelight (in the case of black and white works), but regardless, in both instances the producer of the work cannot see what is being made as it is being made. That is to say, the producer/artist is working blind within the parameters set up before hand. The producer/artist therefore becomes another instrument in the process (reduced to labor, to a body, to a unit of measure, equivalent to the paper or print processor) and not a conscious creator of the work while the work is being physically produced. This contrasts with the normal way that art works are produced: for example in the production of a painting, the producer/artist is consciously constructing the work—thinking conceptually at the same time they are laboring (such as when they are applying the paint)—hence the producer/artist is making informed choices during the production of the work and their approach to the work may be evolving. Photographic processes are particularly conducive to this a-compositional approach, for the moment of exposure is finite and relatively closed, restricting the influence the producer can have during the process. In other words, once the process of production is enacted, very few compositional choices can be made and the information available to an operator is severely limited.

On Composition, Uniqueness, and Difference:

In the case of these works, composition in the classical sense is impossible because of the complex of aleatory factors involved. Once exposed to light, the paper is processed in an RA4 wide format color photographic processor (in the case of color works) or in baths of chemistry (in the case of black and white works). Since there is no negative and no projected image, the works are unique, and because of this and the chance operations imbedded within the process, they are impossible to replicate exactly. At the same time, because the paper is a standardized readymade object and operates both as a thing being imaged and the material that is receiving the image, each work is ostensibly (by the conventions of photographic image production) a photograph of the same thing—the paper itself. In other words, it is a “print” of a standardized industrial object, and thus all of the photograms are prints of nearly identical negatives (or negatives whose differences it would be quite difficult to argue are significant). It is only the minor variations in conditions—rather than the “original” (the photographic paper) which accounts for the differences between prints of the same series. The difference between works is constituted in the incidental shifts between moments of production, not in the uniqueness of the object being imaged or the means of that imaging. In conventional photographs, such differences between prints would be considered at best issues of connoisseurship, but unimportant in assessing the meaning or historical import of a photograph, i.e. it is common to assess the quality of a photograph independent of the quality of a print. These variations in circumstance are not “significant,” meaning they do not “signify” in any specific way. They do not indicate a meaningful distinction between the circumstances or objects they represent. The photogram works are unique, but essentially equivalent to one another, much as every industrial object produced in series (from a run of photographic prints to cereal boxes) is unique as an object and different from all other objects, even if this difference is insignificant or deemphasized by the way that object is conventionally used.

Non-Abstract Photography:

Even though the works are non-figurative, they are not abstractions, because they are not a schematization of some aspect of the world that surrounds them, but rather are defined by their concrete existence. They are not “of” or “about” some other thing. They are connected to the world by being a thing in the world, not by depicting the world. There is no source material that is being “referred” to in the production of the work. These are not reformations of some original object or phenomena that the thing may be instrumentalized to convey, but rather are a part of the phenomena they themselves describe. Pictorial photographs are abstractions (because pictures are images, and images imply a relation of one object to another in a form of significatory dependence). Pictures are “abstracted” from some element of the world, and through the application of a certain logic of abstraction, that world is rendered in a two-dimensional form. They obey an arbitrary set of conventions for the translation of the three-dimensional into the two-dimensional (for example we do not really see in Renaissance perspective, but in a curved hermetic space; Renaissance perspectival formula is a proposition about vision, not vision itself). This abstraction of three-dimensions into a two-dimensional form has been naturalized to the point where this transformation is largely treated as continuous, which has become all the more ubiquitous due to the automaticization of this process within various optical reproductive technologies.

On Absence, Lack, or the “This has been” of the Photograph:

The automaticization of optical images, along with the obfuscation of their material presence (i.e. their meaning in the moment of the here and now) has turned the notion of representation into a form of melancholia, instrumentalizing photographs as evidence of something that is missing. If we treat a pictorial photograph in a conventional manner, speaking to what we assume it is a likeness of, we experience the referent of the image as an absence. According to this interpretation, if someone takes a photograph of a clock, the exact moment and object referred to in the image will always be absent, never to be reclaimed. Even if the object is present, the moment the photograph was made is missing, thus the photograph serves as evidence of something absent. This is the problem with the widespread application of the terms “picture” and “image;” they emphasize what they are not and deemphasize the object in front of the viewer itself along with the conditions of reception of the work.

These works do not refer to something that is absent; they do not gain their significance by "representing" some place or moment at a remove from the viewer, for the probative value of such a thing or moment is minimal, and the thing imaged is present before the viewer. Instead their significance (i.e. status as signifier) is dependent on an infinite procession of moments, and the succession of uses the work is put to in its exhibition, display, and distribution. Any standard, lens-based, figurative photograph is necessarily “abstract” in the technical sense of the term if we describe it based on what it carries a likeness of, this process has just been automated and imbedded within a technology, and thus achieves a false concreteness. Since this separation of sign from signified does not exist in the non-pictorial photographic works, they are never true abstractions, regardless of their appearance. This type of art object should be referred to as “concrete” and “literal,” as the viewer is always presented with the referent and the image at the same time. They are concrete photographs (with a lower case “c”), not abstract or pictorial photographs.