Improvisation and the Agency of the Commons: Notes on Counterfeiting as a Form of Radical Speech

Walead Beshty

First published in Zhijie Qiu, ed., Reactivation: 9th Shanghai Biennale, ex. cat. (Shanghai: Shanghai Contemporary Art Museum, 2012); Revised and expanded in Always Different, Always the Same: An Essay on Art and Systems, ex. cat. (Chur, Switzerland: Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur, 2018).

MaDonal restaurant in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq

What is property? ... Property is theft

—Pierre Joseph Proudhon[1]

1. The Aesthetic Commons

Language and aesthetics are chief components of the commons, they refer to a set of activities and procedures that arise from a body politic that continually invests, innovates, and shares in its utility. In language, the deployment of new or novel ideas often precipitates new or novel formulations of its conventions (i.e. grammar, semantics). The momentum required to innovate or transform language is a matter of bodies and the accumulated force of usage they bring to bear: micro-transformations in the short term produce large-scale changes over time. Aesthetics—understood in the Greek sense as the means by which something becomes perceptible to the senses—relies on a similar mechanism for development: it requires legibility, or “sensibility,” and thus is steeped in convention (the conventions by which things are perceivable to the senses). These conventions bracket innovations and improvisations giving them structure and intelligibility. In both instances the catalyst for change is communal, and these communications are always material; each involve effects on matter, from vibrations in the air to words on a page. In short, all communication involves the informing of specific materials in a manner intended to activate embodied comprehension. Like language, aesthetics is recombinatory, and involves repurposing existing elements into new arrangements. Unlike language, whose complex and regionally specific conditions limit access, aesthetics primarily depends on a condition of embodiment and sensation for comprehension, and less so on a complex codified set of rules; broadly speaking, aesthetics can be trafficked and expanded at speeds language cannot. Furthermore, aesthetics never requires direct person-to-person contact for reception, nor the active acceptance or willful participation of communicants. Thus, the acquisition or comprehension of a set of aesthetic conventions does not impose the same high barrier to entry as language does.

Within this model, the field of language never escapes the field of aesthetics, whether conveyed as sound, in text, or in gestures. In its transmissible forms, language is a subset of aesthetics. It has a narrower set of conventions and modes of expression, and the enforcement of these conventions is often through the active exclusion of deviant forms, as opposed to aesthetics where its exclusivity is most often tacitly expressed, and fungible. This makes language a significant, yet conditional expression of aesthetics. Furthermore, it makes sense that language conceives of itself as self-similar to the law; law acts as a mise en abyme of language, i.e. language sees a model of itself in law, as much as law is formulated and enacted by its expression as language. Law is language reinforced by the sovereign mandate, and law has similar regional idiosyncrasies as language, a similar precedential mechanism for development, and a similar formalized resistance to change.

The structure of innovation and deviation within the broad set of conventions of aesthetics involves not only what and how something can be said or expressed, but also who can speak and who is spoken to. This is what Jacques Rancière describes as a “distribution of the sensible,” noting, “[t]he distribution of the sensible reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community... it defines what is visible or not in a common space, endowed with common language etc.…”[2] This is the fundamental condition of aesthetics, and that which makes it political at its core; in its establishment of a shared zone of “sensation” it creates something held in common linking individuals together, and by doing so, it also constructs exclusions, i.e. those for whom a particular sensate comprehension is not available for one reason or another. In this, it is an originary form of the commons bounded by knowledge and comprehension (not by scarcity or physical limitation), and this boundedness defines a polis. It is a sphere of politics within which all participants contribute to the establishment of meaning and use (i.e. value). The exclusions and inclusions within aesthetics are continually evolving, yet in the aesthetic field those included and excluded evolve according to its own logic without mandate from above. That is, aesthetics is a form of politics that is not defined by the state (i.e. one can speak French, without being a citizen of a state for whom French is an official language, or more exactly, one can be a human being, fully immersed in the linguistic and aesthetic discourse of human beings, but have none of the protections the state guarantees to both its citizens and aliens [state classifications of human beings], as in the case of the detainees in Guantanamo Bay, or those designated as chattel, as in slavery). Aesthetic differentiation might have initially been coterminous with the law of the city-state in ancient times, but it has through human development exceeded the boundaries of the state; it transcends state boundaries and unites individuals beyond the confines of the state. That is not to say the state does not make itself felt in the aesthetic sphere, but the inclusions and exclusions that aesthetics produce are not dependent upon the sovereign mandate; its borders evolve without state sanction.

It is necessary to look to various instances in the contemporary world where the juridical and the aesthetic are in conflict, for when there is such a conflict, it shows the sovereign abstraction—defined within democracy as an expression of the will of the people—to be in conflict with the public good it is intended to reflect. This occurs when something viewed in juridical terms is deviant, but when considered aesthetically is conventional. Use and reuse occurs without bounds within communication; individuals repurpose phrases and construct new meanings all the time, but within the legal system there are clear and present restrictions to this activity, ones that fall outside of standard protections of citizens against harm. It is at the intersection of such competing expressions of the theoretically similar agendas of law and aesthetics that one finds productive models of resistance to the tyranny of the state (i.e. when the state is subject to a misunderstanding of itself as more than a sum of its people), a challenge to its impositions upon the commons on behalf of private actors to whom it grants advantage. These are sites where aesthetics informs us of the ethical lapses of the state.

2. Property and Speech

The idea of property embraces the absolute right to exclude.[3]

—Richard A. Epstein

A right is always against one or more individuals.[4]

—Morris R. Cohen

The commons is an active site of shared investment and collective right, it is not simply a territory that is awaiting privatization or the expression of individual rights; as the political scientist C. B. Macpherson observed, “The fact that we need some such term as ‘common property,’ to distinguish such rights from the exclusive individual rights which are private property, may easily lead to our thinking that such common rights are not individual rights. But they are.”[5] In other words, common property is valuable even if not priced, and constitutes an affirmative preexisting individual right to use, not merely a terra incognita for the assertion of exclusive individual rights and the expansion of private interest. As such we should not discount the harms of private infringement on the commons as being “victimless,” or assume the infringement of the commons is without cost because its properties may not have been traded within a market. In the commons, the granting of private rights to an individual is the stripping of those rights from a multitude of other, albeit anonymous and often legally unrepresented individuals: such parties are often denied legal status, but nonetheless are contributing members of the increasingly global commons and its attending foundational rights. The abridgement of these individual rights produces tangible harms, which are felt across a society as a whole.

This text looks at a certain broadening of property rights into the field of aesthetic discourse. Property rights—initially posited in relation to land and immovable goods (real property) and expanded to moveable goods (private property)—are inserted into the field of communication with the establishment of intellectual property, and its further extension and distortion into the trademark, a precedentially established body of law that directly abridges speech. As the legal scholar Felix Cohen put it in his 1935 essay “Transcendental Nonsense and the Functional Approach,” in the Columbia Law Review:

There was once a theory that the law of trademarks and tradenames was an attempt to protect the consumer against the “passing off” of inferior goods under misleading labels. Increasingly the courts have departed from any such theory and have come to view this branch of law as a protection of property rights in diverse economically valuable sale devices … [6]

Cohen is here referring to the legal test of “confusion” applied within trademark infringement cases, an extension of the common law notion of “passing off”—the central criteria for evaluating claims of infringement up until the early twentieth century—and the subsequent lowering of this threshold to be more broadly inclusive, which tacitly established broad property rights to trademark holders that were akin to those governing private property. This reevaluation and expansion of trademark law was, at the time of Cohen’s text, achieving newfound momentum. He continues:

The current legal argument runs: One who by the ingenuity of his advertising or the quality of his product has induced consumer responsiveness to a particular name, symbol, form of packaging, etc., has thereby created a thing of value; a thing of value is property; the creator of property is entitled to protection against third parties who seek to deprive him of his property … The vicious circle inherent in this reasoning is plain. It purports to base legal protection upon economic value, when, as a matter of actual fact, the economic value of a sales device depends upon the extent to which it will be legally protected. If commercial exploitation of the word "Palmolive" is not restricted to a single firm, the word will be of no more economic value to any particular firm than a convenient size, shape, mode of packing, or manner of advertising, common in the trade. Not being of economic value to any particular firm, the word would be regarded by courts as “not property,” and no injunction would be issued. In other words, the fact that courts did not protect the word would make the word valueless, and the fact that it was valueless would then be regarded as a reason for not protecting it.[7]

Cohen’s statement is significant for a number of reasons. First, it notes the cleaving of trademark from its basis as a limited property right, which protected the consumer from deception or “confusion,” and the transformation of this limited right into a broad protection of the trademark itself as an exclusive property. This is a significant reversal because it describes the transformation of a public right to honest representation in transactions, a right that facilitates a well-functioning market, to a right of exclusionary possession that bars access of a public to a particular signifier. This is a shift from a protection of a public from private parties who are bad actors and seek to misrepresent themselves, to a protection of private parties from the public (this is evident in the case law, wherein the use of trademarks in organized acts of protest against their holders have often been prevented, despite the trademark being repurposed as a form of political speech).[8] Through construing the trademark itself as a property from which a public can be excluded, a part of the commons is transformed into a property held by a private entity.

Secondly, Cohen shows that the court manufactures the economic value (price) of this property by conferring upon it exclusivity, and he emphasizes the circularity of the legal logic behind the protection of such intangibles as private property. In short, the court claims the value of the trademark as a prima facie condition of its decision to protect the value of an investment made by an entity in the trademark, and yet the trademark’s capacity to store economic value is viable only after the legal protection of the trademark takes place. This is what Cohen calls, “the ‘thingification’ of property,”—legally protecting something that previously had limited status as a property and is then transformed into a discrete property by the law. Thus the protections confer a stable “shape” to intangibles in order to make them exclusive, or more “private property-like.” As he continues,

What courts are actually doing, of course, in unfair competition cases, is to create and distribute a new source of economic wealth or power. Language is socially useful apart from law, as air is socially useful, but neither language nor air is a source of economic wealth unless some people are prevented from using these resources in ways that are permitted to other people. That is to say, property is a function of inequality … Courts, then, in establishing inequality in the commercial exploitation of language are creating economic wealth and property, creating property not, of course, ex nihilo, but out of the materials of social fact, commercial custom, and popular moral faiths or prejudices.[9]

The courts and international bodies’ protection of trademark encourages unbridled investment in those trademarks by firms, a phenomenon apparent in the rise of global brands in the twentieth century. Most importantly, it imposes the exclusionary right of property upon the open field of aesthetics, impinging on the means by which a vital form of community is established and maintained among a public.

3. The Effects of Intellectual Property

One problem produced by trademark law, and the further development of the concept of trademark dilution, is that it creates a greater incentive for the allocation of assets to the development of the trademark as a store of economic value, i.e. it increases its stability as a site of wealth accumulation, exacerbating and formalizing the infringement on the rights of individuals to participate in the commons. Put more pointedly, trademarks infringe on individuals’ ability to be among the polis, among the counted, for their right to “use” certain signifiers is abridged, thus barring them from the associations and communion possible through the use of those signifiers; the more ubiquitous or dominant the brand in the public sphere, the greater the abridgement of public discourse. For language is not a finite resource, and rationing cannot be a justification for strict protections; trademark law artificially creates scarcity through the imposition of exclusions. It denies the legal subject full access to the community produced by the free flow of communication and encourages the owners of trademarks to pursue the expansion of the rights given to them. This is how the laws of trademark not only preserve an abuse of the commons, but also incentivize the expansion of those abuses.

There is a further burden this produces, for as trademark infringes on the public use of something held in common, it burdens the holders of this supposed property by insisting that they actively exercise this property right in order to maintain it. It demands exclusion by making the trademark conditionally valuable based on the active pursuit of exclusion by the holders of a trademark. By not enforcing trademarks, corporations are jettisoning some portion of profits available to them, profits which they are legally bound to their shareholders to protect. This pairing of a legal and economic demand places trademark holders in a schizoid position, for the expansion of brand recognition and its seeping into public discourse is the necessary condition of its becoming more valuable; the knowledge and value of a trademark expands through the free flow of public speech. Corporate interests must pursue those that infringe upon their copyrights and trademarks enough to maintain ownership, but not so much that they stifle the growth of their brands in the global marketplace. For example, in emerging markets, the first expression of brand identification usually occurs through piracy and counterfeiting, as these markets are usually unable to support the price point of foreign brands and market presence in daily life is impossible to achieve through standard importation practices alone; simply producing cheaper products for these emerging markets would countermand the exclusivity and luxury of their core brand identity. What we tend to see first in emerging markets are knickknacks bearing the logos of various luxury brands. Thus, counterfeiting circulates knowledge of the status of these brands in advance of their ability to fully enter a marketplace. As a brand first circulates into a new system, especially within an emerging market where standards of living are lower than the country of origin of the brand, the first stage of adoption and brand awareness is facilitated by such infringements on their trademarks. This is how brands like Hermès might be widely known to a population whose mean wages for a year are less than its least expensive handbag. American and European fashion brands actively use this tactic as a means to enter new markets, a key step in constructing an aspirational value for those brands, long before they can directly capitalize on those markets.

This leads to the second issue, that the laws protecting trademark and copyright encourage the consolidation of wealth within markets, driving out small and mid-sized producers. Traditionally, the owners of trademarks that become the most wealthy and powerful are also best able to walk the tight rope of enforcement and tacit acceptance of certain strategic infringements. This process leads to a consolidation of brand power and a geometric expansion of private control over the public sphere: in short, the more valuable a particular brand becomes, the more resources become available from public and private sources to control its use. This creates a further consolidation of power within those already powerful brands. Consider the sheer scale of resources necessary to bring or defend against civil litigation over trademarks, or to lobby governments to take criminal action against counterfeiters, or to protect their brands by including intellectual property protections in international treaties or in the formulation of the policies of the World Trade Organization. This process further favors large producers, facilitating the consolidation of these rights in the hands of major multinational corporations with the means at their disposal to protect intellectual property, while it systematically strips these rights from individuals according to their respective abilities to publicize and defend their rights from infringement. The economic impacts are clear: in the early 1970s, 20% of the valuation of Fortune 500 companies was comprised of their intellectual property holdings. That number is now reversed. Furthermore, intellectual property is primarily consolidated in the United States and Europe, and is far less dominant in the valuation of corporations in developing countries.

In response, individuals innovate to avoid the harm intellectual property protections cause, constructing communities that systematically evade restrictions on trademark. Public behavior can be understood as a symptom of a substantial underlying harm in this respect, the more common or developed a response to a particular abridgement of rights, the more evidence of undue harm is being expressed. The decriminalization and legalization of marijuana in the United States is a clear instance of this, as the widespread use of the drug made the draconian enforcement of drug laws increasingly untenable, inconsistent, and unequal, yet the decades of suffering produced by these anti-drug laws are an incredibly high price to pay, and moreover, it is a price that is largely borne by the poor and the working class further exacerbating wealth disparity.

Another fundamental problem presented in the transformation of speech into property through the protection of intellectual property (particularly that of trademark law) is that the valuation is one-sided: it values the investment into brand identification “created” by corporations, while neglecting to price the value created by the consumers of that brand within the commons. Brand identities are constructed and strengthened by users and their activities. In giving brands independent or discrete economic value and defending corporate owners as the sole creators of the brand’s value, the courts discount or obscure the work done by consumers to build that brand in the commons. Each time the brand identity is thought, spoken, or displayed it is changed or added to by individuals—they repurpose, reconfigure, and redistribute it. This can often rescue a brand from economic collapse. Consider how the brake and gas pedal design, which lead to the “unintended acceleration” that ended the run of the luxury Audi 5000 in the United States prompted the use of the slang “Audi 5000” (meaning to leave abruptly), promoting the luxury the brand represented, and normalizing its idiosyncrasies in one gesture. This popularization led to the circumstances that allowed Audi to reestablish itself in the luxury car market as an aspirational brand redeeming its product line, as the use of the phrase produced the immediate effect of widespread awareness and cultural currency of a brand that had previously been only a niche product. The modifications that brands are subject to is a form of redistribution and repossession of their meaning that often increases their value and cultural influence. That the sole rights and benefits are conferred upon the holder of the trademark translates into an annexation of a portion of public discourse for private enrichment, even as the value that this public discourse confers upon brands contributes to the wealth and power of its private owners who may wield it over their trademark as they see fit.

4. Counter-Networks

The following is a loose case study in just such a mode of production that moves within yet is opposed to the traditional management of the aesthetic sphere by the state: counterfeiting, that very field which is rendered external or marginal due to the enshrinement of intellectual property.

To begin with, the term “counterfeit” contains within it a fundamental note of political resistance, originating from the Old French contrefait, derived from the Latin contra- (in opposition) and facere (make). The earliest known counterfeits were produced in the south of France, then a part of Roman Gaul between 30 and 20 BCE. French locals emblazoned wine stoppers with hash marks standing in for the names of Roman producers, filling the bottles with cheap local wine and passing them off as the sought-after imports. This burgeoning circulation produced the powerful wine traditions seen in the region. Evident in this early form of systematic counterfeiting is a population’s resistance to occupation, a response to a set of values and laws imposed on them by an external state mandate that is against the will, and good, of the governed. This type of systematic resistance serves the purpose of relieving a population from the overreach of a state power and frequently is the first expression of an emergent productive logic, as evidenced by the strength, complexity, and innovation of the wine making regions in the south of France, who rather ironically now funnel their significant power into policing counterfeiting.

Fig. 1

The exploitation of either unpriced, or undervalued resources by an external power is fertile ground for the development of counterfeiting economies. Those companies who either license their brand or produce their products abroad are most vulnerable. Apple Inc., for example, saw a huge explosion of counterfeit devices entering the market a short time after they relocated their production to China—this piracy expanded even to the establishment of counterfeit retail locations (figure 1).[10] The availability of authentic parts (which are often used in tandem with other components), in addition to the local presence of expertise in brand operation and its products, makes their counterfeiting that much easier, increasing the quality and prevalence of counterfeits. All of this has boosted Apple’s brand identity in China, and made it one of the most instantly recognizable brands in the country. Despite the goods themselves being well beyond the reach of average citizens, many individuals own items with Apple logos, making the brand name almost ubiquitous. In outsourcing production to countries with cheap labor, poorly maintained working conditions, and few of the human rights protections of their countries of origin, minimize their production costs. Brands such as Nike, The Gap, Gillette, and Apple, make use of such conditions, but exploiting the flexibility allowed in the global marketplace works both ways, subjecting their brand identities to a similarly flexible zone of use. A case in point is that the most frequent counterfeiters are those factories that once produced goods for a particular brand, but lost the contract, often as a result of being underbid by another factory. Feeling the pain of competition within capital markets, the response of these one-time sanctioned producers is an equally capitalistic exploitation of available resources. Already in possession of parts, knowledge, and experience with the brand, they are uniquely capable of producing knock-off products with a high degree of fidelity, and in addition, can extrapolate logical extensions of the brand identity, producing new goods with highly convincing logos and designs. Each brand weighs these potential costs against the savings produced by exploiting systemic inequalities between populations. It is also a form of protest against the policies of these brands, acting against their ability to leverage their economic power to maximize profits at the expense of regional workforces. This is not simply a problem related to emerging markets, several examples can be found within the United States where forms of piracy as political speech, especially among historically repressed classes, have had to be accepted by trademark holders.

For example, in the early 1990s, the New York Times reported the following:

From Harlem to Watts and nearly every urban enclave of black youths in between, black variations of the popular cartoon grade-schooler, Bart Simpson, have been the most enduring T-shirt images of the summer … “There is a suppressed rage in the cartoon that black people are picking up on,” … Ultimately, the reasons for the popularity of the black Bart character may be as elusive as determining where the great masses of T-shirts come from … none of the Black Bart T-shirts are licensed by Fox … [11]

Fig. 2

The Washington post had this to add:

One eyewitness tells of a hot new black Bart T-shirt on the streets of New York City: South African leader Nelson Mandela is standing over Bart, who’s saying, “He’s my hero.” … The only street phenomenon similar to this, in recent memory, was the bootleg, Afro-Americanized Mickey and Minnie Mouse T-shirts of a few years ago (“Yo baby, yo baby, yo ... ”). But that was peanuts compared with the unmitigated appropriation of Bart Simpson. [12] (figure 2)

The speed with which acts of appropriation spread is indicative of its potency as political speech, which in this case addresses prevailing inequities in representation (the whiteness of cultural products, and the absence of people of color within mass media), and moreover, such counterfeiting operations are able to outflank most attempts at quelling it both by the dynamic speed with which they act, as well as the dispersion of the counterfeit products across a large field of small scale producers. Twentieth Century Fox, holder of the Simpsons trademark, had to accept that they could not shut down the illegal usage of their brand; as the Simpsons’ creator Matt Groening described, “There have been busts all over the country.”[13] Twentieth Century Fox could only demonstrate attempts to preserve their property rights in the eye of the law, and wait out the trend. Still, the lost revenue represented by the bootleg T-shirt sales they did not profit from (and this is debatable, since Fox never produced any “Black Bart” T-shirts nor planned to do so) is far outpaced by the increased value, currency, and viewership the brand acquired through the widespread improvised use of their trademark.

In the late twentieth century, the international trade in counterfeits exploded as enforcement reached its apex with the tide of globalization, that is, as common markets and offshore production reached new heights due to the myriad technological and infrastructural improvements that gave firms access to new consumers and cheap labor on distant shores. Like all emergent logics, the counterfeit trade is considered parasitical from the perspective of dominant power centers, a deformation or contamination of commerce. Yet, the counterfeit economy is a glimpse of a world in its becoming, the harbinger of a new balance of power and the emergence of a radical capitalism from the ground up, a vibrant market of competing micro-producers realized on a scale that grows in proportion to expansions of global trade and hegemonic corporate interests. It develops in direct opposition to the state-sponsored oligopolistic corporatism which is all but ubiquitous in the contemporary world.

China presents a compelling model of an emergent resistance to the transformation of public speech into private property, as it is both one of the largest sources of counterfeit items in the United States and Europe (variously charted as 60–80% according to government agencies and NGOs), and due to its scale, has the longest and most studied traffic in such goods.

5. General Classifications of Chinese Counterfeit Goods

• In Mandarin Chinese, counterfeit goods are referred to as jia-huo, fang-mao-pin, or the more formal, jia-mao-chan-pin.[14]

• Jia-hou, fang-mao-pin, jia-mao-chan-pin are generic terms for ‘counterfeit goods,’ and are used inclusively to refer to a number of different types of counterfeiting or bootlegging. Within this category, anthropologist Yi-Chieh Jessica Lin offers the following classifications.[15] Ke-long is a transliteration of the English word ‘clone,’ and refers to goods that emulate an existing product. Bang-ming-pai, is a good which a particular brand does not make but is consistent with the brand’s internal logic. The term can be understood by separating it into its constituent signifiers: bang meaning ‘next to’ and ming-pai meaning ‘brand names.’ Thus the term refers to adjacency rather than duplication. Shan-zhai goods are the most transformative—modifying, adapting, and reconfiguring brand identities in ways radically inconsistent with the original. Unlike the other terms, Shan-zhai has explicit political implications, and constitutes politicized speech. While these terms are loose, as classifications they usefully isolate various methodological differences between the various articulations of “piracy,” particularly their effects on the dominant aesthetic practices with which they intersect. Furthermore, they can be useful in distinguishing the circulation, means of production, and meanings associated with each approach.

Fig. 3

• KE-LONG is a simulated or copied (cloned) good that is reverse engineered from the original and is meant to replicate that item. The source of distinction among these products is their respective fidelity to the original, which is a function of their access to the original designs, quality and cost of materials, technical complexity, and the labor intensiveness of the fabrication. In the jargon of counterfeit sellers, Ke-long goods are broken down into B, A, AA, and Super AA. (figure 3)

B: common, and easily distinguishable from the original because of the use of low quality materials (such as plastic instead of leather), and obvious deviations from the original’s design and appearance.

A: not immediately distinguishable from the original but has poor quality finishes, and cheap material substitutions (such as low-grade leather, chromed hardware, substandard fabrication and so on).

AA: higher quality materials and fabrication than the A level but still not of the same quality as the original (for example, high quality leather yet divergent interiors, incorrect stitching etc.).

Super AA: exact copy of the original in both materials and detailing.

Fig. 4

Even Super AA versions contain some deviations from the original, and these become greater as one approaches the B level. Yet each category contains within it unique attributes, for example the interpretive choices of material substitution; thus, each copy has unique traits. This shift in fidelity offers increased insight into the nature of the counterfeit good, at times indicating regional origin, and it is possible to discern from their detailing which elements of the original are most highly prized as being marks of authenticity and value for the particular maker. Even this category, despite being premised on being a direct copy, is “interpretive”, leaving a fingerprint of the how the characteristics of a product were adapted to the means and resources available. As one descends to the B level goods, basic templates for production become clear, generic riveting, standard thread counts, or a patterning, in addition to the material consistency of the low-grade copies between various brands produced by a single maker or specific region. This restriction of means causes certain aspects generic to the class of object to be privileged over others. The result, in each instance, is a kind of abstraction of the original, derived from the particular constraints the producer faces. (figure 4)

Fig. 5

• BANG-MING-PAI is when the brand or brand logo of a particular producer is affixed to a good that shares affinities with but is not an exact replica of an actual product of that brand. These are most commonly products for which it seems plausible that a particular brand might produce it or something similar, but in fact does not. For example, underwear with Gucci logos on it—a product Gucci does not make but which is not far removed from the products it does offer within the apparel space. (figure 5) Sometimes these goods are combinations of multiple products distilled into one, as in a single counterfeit Chanel handbag that has details drawn from multiple different handbags produced by Chanel. These are extensions of brand identities into new product lines, and involve a greater degree of interpretive abstraction of a brand’s identity, as opposed to ke-long goods whose deviations revolve around material scarcity and cost restrictions.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

• SHAN-ZHAI indicates an instance of improvisation with regard to the brand identity, either bringing it into unrelated fields—for example a purse or stove with an Apple logo on it (figures 6–7)[16], or a Louis Vuitton cell phone (figure 8), or the production of goods under a brand name which is slightly different that the original, such as Sumsanc, iPhane, T-Phone, NCKIA, or SAXNUG. (figure 9) Non-English speakers may not notice the deviations in the brand names, see them as minor, or even as a willful defacement of the brand identity. Furthermore, the term literally refers to a ‘mountain fortress’, and, in this usage evokes the idea of bandits living in mountain strongholds who sustain themselves by robbing from the wealthy valleys below. For this reason, Shan-zhai has overt associations with revolt, resistance, and piracy. In a contemporary context, it also has anti-colonial undertones. Beyond this, Shanzhaiism as a philosophical position is much like the French term Bricolleur, a tinkerer who composites things in an unsanctioned manner, appropriating useful elements and recombining them into an improvised and often provisional form. Shan-zhai products are often short-lived and transitional, and many Shan-zhai producers go on to establish unique product lines unrelated to piracy.

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Shan-zhai is thus the most radical and disruptive category of the counterfeit, as it transforms and regionalizes brand identities with an eye to the overturning of their dominance and redirecting or reconfiguring the meaning of these brand signifiers. In short, it treats trademarks like slang, reversing, transforming, and transcending the original meanings of brand identities to produce new innovative forms. This form of “slang” or “patois” is no less vital, or significant, as a form of political speech, and should not be discounted or disqualified from the category of political speech simply because it realizes itself in commercial goods (increasingly, even the courts have protected economic relations as a form of speech in the United States).[17] In this light, Shan-zhai goods function similarly to that of a minor language, as posited by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, which they describe as “that which a minority constructs within a major language.”[18] As they explain, “Minor languages are characterized not by overload or poverty in relation to a standard or major language, but by a sobriety and variation that are like a minor treatment of a major language … deterritorializing the major language.”[19] In fact, the very embeddedness of counterfeiting in the sphere of economic exchange is the source of its strength and legitimacy as speech—it reclaims both meaning and economic self-sufficiency from a globalized market place, and constitutes a reaction against economic and semiotic colonialism.

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

6. A Short History of Shan-zhai Products

In 2003, Chinese automaker Chery (an overt play on the name Chevy) released the QQ model, an imitation of the Daewoo Matiz, which was set to be marketed in China under the name Chevy Spark. Beating the Chevy model to market and selling the model at half of the sticker price of the Chevy, the move, while evoking associations with the American automaker, successfully kept Chevy a minor player in the Chinese auto-market for the next decade (figure 10). The two cars were virtually identical, down to the doors; it was soon found that the QQ passenger doors were interchangeable with the Spark.[20] Similarly, the automaker BYD (Build Your Dreams) began by emulating BMW’s logo and product line when it emerged in 2003 (their G3, and Haifeng, for example, was similar to the BMW’s compact 3 series, and the G8 incorporated elements from Mercedes product line). It has since moved on from this strategy, and is now the largest producer of electric cars in the world with an independent product line. (figure 11)[21]

The most prevalent Shan-zhai product is cellular telephones, a market which erupted after “Taiwanese cell phone chip designer MediaTek developed and marketed low-price, multifunction cell phone chips to Chinese cell phone workshops beginning in 2006.”[22] After that time, it became possible to simulate and innovate a line of cell phones on a relatively modest scale, opening up the market to small producers operating in regional or isolated markets. It also created a huge variability in the range of products created, each factory responding to local demands, or individual factory manager’s idiosyncrasies. This lead to MediaTek’s chairman, Ming-Kai Tsia to be referred to as the “Godfather” of the shan-zhai cell phone industry.[23]

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

The power of the shan-zhai makers in China is illustrated by the shan-zhai cell phone called the “AnyCat,” modeled after Samsung’s “AnyCall.” A touchscreen phone, the AnyCat had achieved a high level of popularity, selling for one-fifth the price of the AnyCall (figure 12). Samsung found the AnyCat to be superior to their product, offering functionality that the original lacked. Samsung then approached the company and proposed a collaboration, which was refused.[24] A similar challenge to the established cellphone industry was represented by the cell phone maker GooPhone, this time to Apple Inc.. The term “GooPhone,” is a transliteration of gǔ fēng; literally: “valley peak,” a rather obvious allusion to shang-zhai. One of many manufacturers of iPhone clones (they continue to offer cheap versions of every new iPhone released, including the most recent iPhone X for which they launched the GooPhone X) GooPhone threatened Apple with copyright infringement if they began selling the iPhone 5 in China, since they had applied and received patent rights for the phone’s design prior to Apple’s being able to secure them within China (figures 13–14).[25]

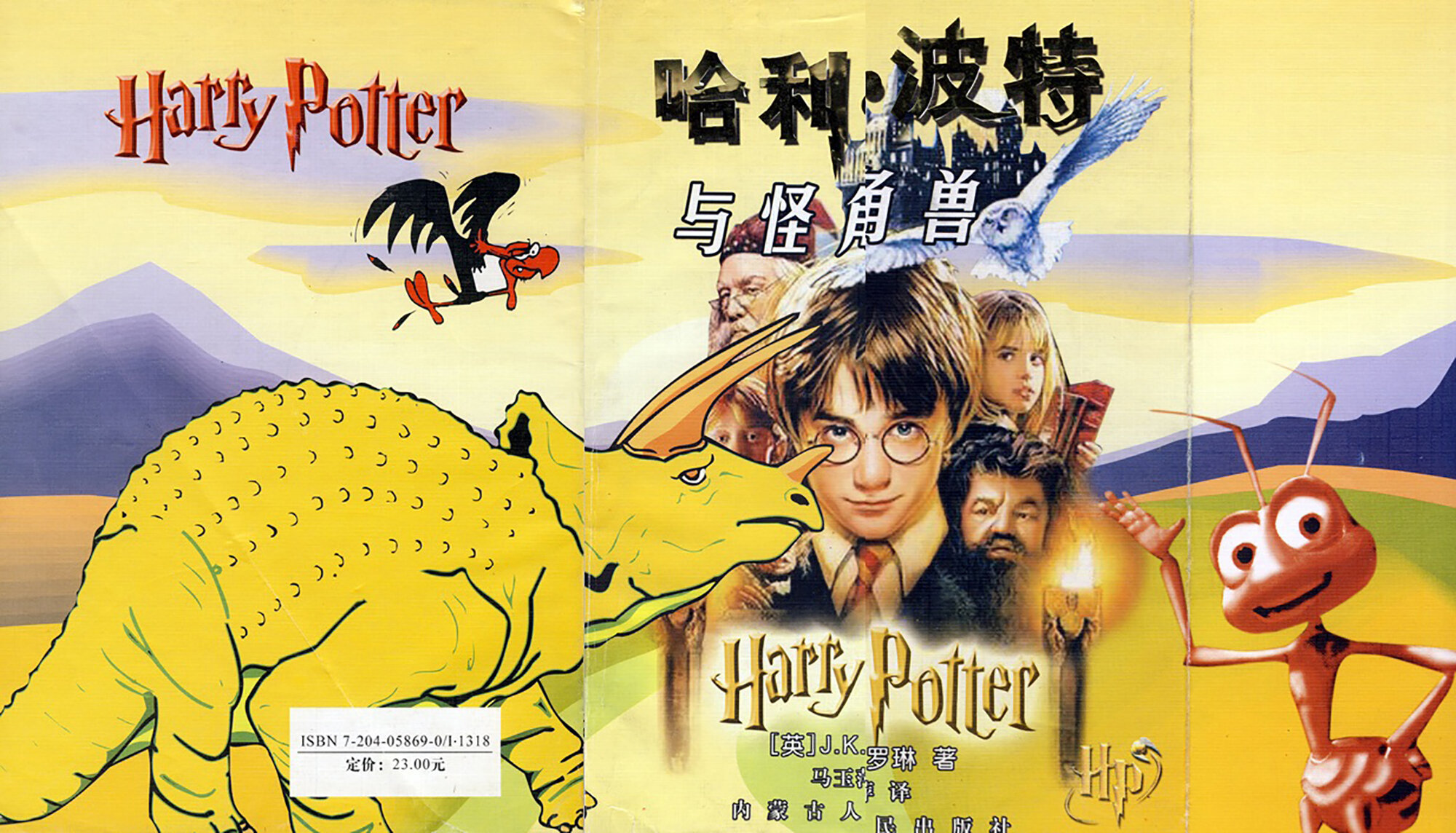

Fig. 15

These improvisations include new creative works, such as shan-zhai iterations of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter franchise, a particular favorite of Chinese shan-zhai producers. In advance of the release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows multiple versions of the book arrived on Chinese store shelves weeks before its official release. These spanned from straight copies to wholly new works of fiction using the Potter characters. (figure 15) As the New York Times reported in 2007,

these unlicensed books, include “Harry Potter and the Half-Blooded Relative Prince,” a creation whose name in Chinese closely resembles the title of the genuine sixth book by Ms. Rowling, as well as pure inventions that include “Harry Potter and the Hiking Dragon,” “Harry Potter and the Chinese Empire,” “Harry Potter and the Young Heroes,” “Harry Potter and Leopard-Walk-Up-to-Dragon,” and “Harry Potter and the Big Funnel.”[26]

or evident in the multiple unsanctioned “translations” of Bill Clinton’s memoir, My Life. One of the most popular was rewritten with the former president as an avid (and perhaps obsessive) fan of China, as in this excerpt:

Ever since I was little, I yearned to go to China. I thought it must be a mysterious and special place. Whenever I saw one of the cannons Buddy tested being fired, saw the force with which the shell came whistling out, I would think how incredible the Chinese invention of gunpowder was. Hillary’s mother could tell that her future son-in-law was a simple and honest man, likable and easy to get along with. She specially poured me a big glass of mineral water, and added some sugar, saying, “Now, can you tell me what you know about the philosophical traditions?” Encouraged, I said, “Chinese philosophy, Indian philosophy, and Western philosophy, which later originated in Greece, can together be called the three great philosophical traditions.”[27]

Another pirate translation that came on the market in 2004 recounts how Bill Clinton, in an effort to impress Hillary Rodham while they were courting, bragged that his childhood nickname was “Big Watermelon.”[28] While they are neither parody, nor simple clumsiness, these and other expressions overall display irreverence for brand identities, which in much of the developed world would be regarded as sacrosanct.

Fig. 16

7. An Emergent Radical Capitalism

The characteristics of the Shan-zhai marketplace resonates with the vision of capitalism set forth by Adam Smith, as a field of small producers, generating differentiated products, and operating in direct competition with one another. This model of capitalism, what economists call pure monopolistic competition, is anathema to the current model deployed in the West that privileges oligopoly, the dominance of a market or industry by a small number of large scale firms, who collude with one another and governmental agencies tasked with their oversight, to create extensive barriers to entry. As mentioned earlier, intellectual property is key in the oligopoly protecting practices of Western governments, for it favors those who have amassed the power to enforce their rights, lobby governmental authorities, and affect international treaties relating to trade, which not only creates increasingly rapid consolidations of market power but privatizes the control over public speech (figure 16).

Smith himself was anti-oligopolistic, commenting that businessmen if allowed would engage in a “conspiracy against the public, or in some other contrivance to raise prices.”[29] In an attempt to squeeze maximum profits out of buyers, Smith speculates that business owners will attempt to usurp the function of the market through collusion or by lobbying for government interventions. As he wrote, the values of

… any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public ... The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention.[30]

This is certainly what is most needed today, as the large-scale collusion between corporations and governments to control global markets is so prevalent as to be an almost clichéd topic of conversation. It is this very collusion—a collusion that disenfranchises those who do not benefit from the movements of global trade, who are exploited as cheap and disposable raw material of brand development—which emergent systems of counterfeiting challenge directly. The irony here is that the threat to capitalism does not emerge from leftist progressives and communist radicals, but from the very tenets of the free market itself.

[1] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, “Chapter I, Method Pursued In This Work—The Idea Of A Revolution,” in What is Property? An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government, trans. Benjamin R. Tucker (New York: Humboldt Publishing Company, 1890). First published in French in 1840.

[2] Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill, Continuum, London 2004, p. 12.

[3] Richard A. Epstein, Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 65.

[4] Morris R. Cohen, “Property and Sovereignty,” Cornell Law Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1927, p. 12.

[5] C. B. MacPpherson, ed., Property: Mainstream and Critical Positions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), p. 5.

[6] Felix Cohen, “Transcendental Nonsense and the Functional Approach,” Columbia Law Review, Vol. XXXV, No. 6, 1935, p. 813.

[7] Cohen, p. 814.

[8] United Airlines, Inc. v. Cooperstock, June 23, 2017, FC 616, https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/fct/doc/2017/2017fc616/2017fc616.html

Mark Davis, “Canada: Protest Site Grounded for Using Adulterated Trademarks,” Mondaq online, August 18, 2017,

http://www.mondaq.com/canada/x/620012/Trademark/Protest+Site+Grounded+for+Using+Adulterated+Trademarks

[9] Chris Morran, “Man Takes Down Anti-Santander Billboards After Bank Sues For False Advertising, Defamation, Trademark Infringement,” Consumerist online, November 14, 2016, https://consumerist.com/2016/11/14/man-takes-down-anti-santander-billboards-after-bank-sues-for-false-advertising-defamation-trademark-infringement/index.html

See also rulings against the use of SAFEWAY and PGA logos by unions protesting their labor practices.

[10] Uri Friedman, “Welcome to China’s Fake Apple Store,” The Atlantic The wire online, July 20, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/07/welcome-chinas-fake-apple-store/353065/

[11] Michel Marriott, “I’m Bart, I’m Black and What About It?” The New York Times, September 19, 1990, at C8, col. 5.

[12] David Mills, “Bootleg Black Bart Simpson, The Hip-Hop T-shirt Star,” The Washington Post online, June 28, 1990, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/06/28/bootleg-black-bart-simpson-the-hip-hop-t-shirt-star/11b3b65d-4033-41da-a5f7-e13ea56ce498/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.eac5c8263040

[13] ibid.

[14] Georgios A. Antonopoulos, Alexandra Hall, Joanna Large, Anqi Shen, Michael Crang, and Michael Andrews, eds., Fake Goods, Real Money: The Counterfeiting Business and its Financial Management (Bristol, United Kingdom: Policy Press at the University of Bristol, 2018).

[15] See Yi-Chieh Jessica Lin, Fake Stuff: China and the Rise of Counterfeit Goods (London: Routledge, 2011).

[16] Deborah Netburn“In China, Apple Makes Stoves?” Los Angeles Times online, February 27, 2012, http://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-istove-apple-knockoff-china-20120227-story.html

[17] See Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

[18] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), p. 16.

[19] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 104.

[20] See Christine Tierney, “Chinese Carmaker Ambitious, Controversial,” Detroit News,. http://www.detnews.com/2005/autosinsider/0501/02/A08-47232.htm.

Frank Williams, “China to Foreign Automakers: Drop Dead” The Truth About Cars online, August 16, 2007. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

“China Chinese Chery QQ – a carbon copy of the Daewoo Matiz,” MotorAuthority online Retrieved July 6, 2006, http://www.motorauthority.com/news/industry/chinese-chery-qq-a-carbon-copy-of-the-daewoo-matiz/

[21] John Voelcker, “China's BYD tops global electric-car production for third year in a row,” Green Car Reports online, February 21, 2018, https://www.greencarreports.com/news/1115398_chinas-byd-tops-global-electric-car-production-for-third-year-in-a-row. See also: Sherisse Pham, “This Buffett-backed Chinese stock is up 55% in a month,” CNN Money online, October 11, 2017, http://money.cnn.com/2017/10/11/investing/byd-warren-buffett-china-electric-cars/index.html

[22] Yi-Chieh Jessica Lin, Fake Stuff, p. 18.

[23] Ibid. p 17

[24] Ibid. p 18, see also: Jane Han, “Chinese Shanzhai Challenges Korean Products,” The Korea Times online, September 15, 2009, http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/biz/2016/12/123_51901.html

Fu-Lai Tony Yu, Diana S. Kwan, Chinese Entrepreneurship: An Austrian Economics Perspective (London: Routledge, 2015).

[25] Chris Matyszczyk, “iPhone 5 clone maker to sue Apple over, um, iPhone 5 patent?” c|net online, September 4, 2012,

https://www.cnet.com/news/iphone-5-clone-maker-to-sue-apple-over-um-iphone-5-patent/

[26] Howard W. French, “Chinese Market Awash in Fake Potter Books,” The New York Times online, August 1, 2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/01/world/asia/01china.html

[27] Alex Beel, trans., “Bubba Tea,” Harpers Magazine, November 2004.

[28] “Bill Clinton’s Fake Chinese Life,” The New York Times online, October 24, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/24/opinion/bill-clintons-fake-chinese-life.html

[29] Adam Smith, “Book I, Chapter X, Part II,” in Wealth of Nations (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776), p. 152.

[30] Adam Smith, “Book I, Chapter XI, Part III,” in Wealth of Nations (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776), p. 292.